The Road to Recovery: What mobility data is telling us about COVID-19 and how it can help us plan economic recovery

Today, we live in a COVID-19 world. The scope of the disease is seemingly endless, the tragedy it has caused is hard to grasp. But, one thing is certain: the pandemic will pass and we will overcome. The effects of COVID-19 stretch far and deep well outside of what we can physically see and visualize. They surpass most of our abilities to predict what a post-COVID-19 world will look like. The news cycle is grappling with the numbers, projections, and trajectories and the big question: when and how will we recover? From what we have learned from natural disasters and economic collapses in the past, we can only presume that recovery will come in many forms and it will be neither easy nor straightforward.

But there is hope. While we do not have all the answers, we do have tools and we have data. More data is created today than thousands of years behind us combined and similar to the rings in a tree trunk, data imprints societal events, reactions, and indications of the future; the more data is created, the imprints obtain ever higher fidelity. Data today is powerful in telling us how COVID-19 is spreading and how it is currently affecting our health, economy, society, mobility, and politics. As we overcome the peak, we now need to start looking at the future. The same data and analytical tools can help us do this and they have been more democratized than ever; if we start to look at our data a bit differently, they will make a measurable difference when we look to define and decide recovery trajectories of different communities and get ahead of stumbles.

“Many officials in government from economic developers, to planners, to political staff, to engineers, might be grappling with the prospect of poor data, lack of data, or perceptions that the data is not tracking the right things.”

More so than analyzing data, now is a time to help others and many officials in government from economic developers, to planners, to political staff, to engineers, might be grappling with the prospect of poor data, lack of data, or perceptions that the data is not tracking the right things. Data acquisition may also be a daunting task as we assume a tighter budgetary environment, not to mention many manual data collection methods are no longer possible with physical distancing such as in-person surveys or traffic counting.

This article explores the idea that analysis to understand and plan community recovery can be derived from, enhanced, and made more resilient by using many different datasets outside of traditional data terms of reference. Especially when traditional means of data collection dry up for reasons laid out above, there are alternatives that are accessible today that are just as insightful. This article offers examples of ways to interpret data unconventionally starting with data you likely already have or are in the public realm that can help illustrate the disease’s impact and chart out a road to recovery. We all have to be enterprising in these uncertain times.

We first look at mobility data, which by its definition retains patterns of movement behavior of different communities like a fingerprint or its own set of tree rings. Mobility in context can describe all facets of a community. It can provide insight across nearly all functions of government beyond traffic and transportation itself, including economic development, planning, finance, transit, public works, etc., leading to providing better services to residents. Here’s why. Understanding how people move over time can help describe how the pandemic uniquely affected different communities and their local economies but it also indicates how to best help communities recover and rebuild.

“Understanding how people move over time can help describe how the pandemic uniquely affected different communities and their local economies but it also indicates how to best help communities recover and rebuild.”

To all government officials reading this, thank you for all you are doing now in these trying times and always. We hope this helps even the smallest bit and if it does not, please tell us what would better support you.

What Mobility Data is Telling us About COVID-19

Consistently across North America, data is telling us that people are driving less now. There are some fluctuations between different communities as physical distancing and stay-at-home rules were instituted at various rates and severities. Many traffic and transportation departments are measuring this trend in their communities with traffic data they are already collecting through sensors or other sources. At face value, this helps traffic and transportation engineers and planners understand how traffic lights might be better adapted during this time, also an modify schedule for road work improvements if construction is still permitted. If we dig a bit deeper and even look at it in context, the same data can be used to answer economic questions around how communities are dealing with COVID-19.

“If we dig a bit deeper and even look at it in context, the same data can be used to answer economic questions around how communities are dealing with COVID-19.”

We took a few sources of mobility data: travel times, traffic volumes/journeys, and commercial truck volumes, that would be comparable and scalable to any jurisdiction. We have given some high level example interpretations of what the trends could mean if you are seeing something similar in your community. These interpretations are theories of the behavioral reasons to why we are seeing increased, persisting declines in traffic and future trends they might be indicating as well. There is no one size-fits-all with these interpretations as communities are so different and unique. The technique is to use data already available and analyze it in context with your community (the grocery stores, the pharmacies, the demographics, the parks and greenspaces) and observe how they behave around each other. The data mix can unveil your own theories about observed patterns that can be further investigated and interpreted to inform a unique path to recovery for each community.

Decreases in travel times are greater in the morning than evening; it tells us a story of COVID-19, commutes, and congestion

Travel time is a measure of how long it takes a driver to get from point A to point B, typically along a segment of road. Travel time can be collected with sensors and GPS but also can be produced by location-based service application companies as they use anonymized locations from apps on phones to ping the number of minutes and seconds it takes to get from A to B. When UrbanLogiq looked at a source of location-based data, in this case Mapbox Directions API, and compared travel times throughout February, March, and April, we saw in a number of communities in Canada and the United States where travel time during peak hours on weekdays in particular have decreased across the board. The decreases recorded in morning peak hours in some areas were up to 58%, particularly on major arterials and freeways, while afternoon/evening peak hours only saw an average decrease of about 12%. Travel times on residential and roads outside of major shopping centers have gone relatively unchanged.

Interpretation: Daily commuting by car is a major contributor of congestion and higher than normal travel times. Today, it is very clear fewer people are driving to work, however, everyone still ends their workday at the same time, which means it is still a natural time of day to drive to the grocery store, the pharmacy, or seek other essential services. Changes in travel time can show where and how to mitigate overcrowding at essential service access points, it can also show us which routes are most resilient or susceptible to smaller changes in volumes and congestion, which routes are most important in carrying people, goods and services, which traffic lights are ill timed making unnecessary blockages, as well as which routes are potentially conducive to added public transportation post-COVID-19. Insights can emerge from understanding travel time, most powerful of which are looked at in context.

Important distinction: travel times can indicate levels of congestion but do not necessarily reflect the number of vehicles, for which volume changes have generally been far more pronounced (see below).

Frequency and volume of passenger vehicle trips can be a pulse of community recovery

San Francisco (56.4% passenger vehicle journey decrease), New York City (-53.8%), Austin (-53.3%), and Seattle (-53.3%) have seen the most pronounced decline in number of passenger vehicle journeys according to wejo, a data company providing connected vehicle and mobility data across the United States (to check out journey changes in your area, please visit wejo’s intelligence hub: https://www.wejo.com/journey-intelligence). Wejo noted that the average drop across the entire United States has decreased by 39.1% as of March 30, 2020. As of April 6, nearly 15% of states are “seeing journey volumes slowly increase again after an initial sharp decrease following stay-at-home orders.” The City & County of San Francisco has since strengthened restrictions of the shelter-in-place order, as many jurisdictions have, so future pulls of the data could show further decreases in the total number of trips.

Interpretation: Aggregated numbers are difficult to interpret as is. With broad-reaching stay-at-home orders, the finding is logical: the number of vehicle trips decreases when people stay at home. The origins and destinations of the trips, however, become more interesting particularly in context which can reveal some of the idiosyncratic needs and behaviours of different neighborhoods during and after the pandemic, for instance: which neighborhoods could be most susceptible to disease spread (by how far reaching and frequent their journeys are), which are well or poorly connected to essential services (by how far they have to drive or how cut off they are with transit options diminishing), and which ones were the economic lifelines of different businesses (by how frequently they travelled to certain destinations and once the pandemic hit, stopped). This can indicate which specific connections a government must re-bolster immediately once travel restrictions have been lifted or potentially incentivise businesses to relocate to better serve underserved communities thus founding both stronger economic opportunities and social cohesion.

NOTE: You might not need connected vehicle data to obtain similar insights in your community. Historical and/or live traffic volumes being collected by traffic departments will be able to show how journeys are changing over different business clusters (industrial zones versus financial centers versus commercial/retail main streets) and over different demographic enclaves in neighborhoods (high income versus low income).

Commercial truck traffic volumes shows changes in supply chain connections as well as inter-community dependencies to freight and goods movement

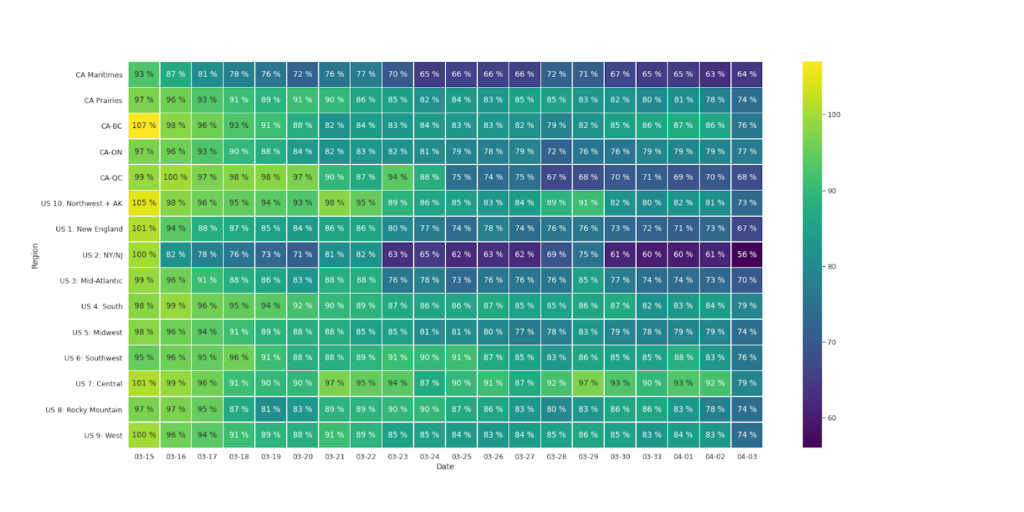

The commercial trucking and freight industry is undergoing significant strain due to COVID-19. It is having to work overtime to deliver on the exponential increase in the demand for essential goods and services (e.g., food, medical equipment, pharmaceuticals) while simultaneously cutting back due to the diminishing demand for other supplies such as oil and gas, restaurant and retail store deliveries, and consumer goods. It is no stretch to claim that supply chains and the trucking industry that sustains them will change in the wake of COVID-19. But how will they change? Data from Geotab, an international telematics and logistics management company, has “identified changes to commercial transportation and trade activity since the onset of COVID-19 based on an analysis of anonymized and aggregated insights from its base of over 2 million commercial vehicles worldwide.” Take a look at the heat map below to see how trucking traffic has changed in your region.

Source: GEOTAB https://www.geotab.com/blog/impact-of-covid-19/

Interpretation: Commercial trucking and freight logistics are supply chains in motion. Global supply chains and international shipping industries in countries that had the COVID-19 outbreak earlier than North America, like China, are now experiencing disruptions. Unfortunately, North America is not immune to downstream effects caused by COVID-19 but continental trucking patterns provided by datasets like Geotab can help indicate exactly which communities and businesses disproportionately depend on the trucking industry and are most susceptible to related downturns.

As stay-at-home orders persist, the role that motorized modes of transportation play in our daily lives will continue to change even as we start to recover and there are many theories of how. Our decision to look at motorized modes of transportation for this article was chosen to demonstrate the changes in motorized mobility patterns can tell us about other potential behavioral changes within different communities and how they will evolve as COVID-19 continues and we eventually begin recovery. Our work will expand to include other data and we encourage readers to think about what data they already have access to throughout their government or agency, no matter how old or how sparse it might be, and use it to look at how it might indicate what is happening in your communities today and tomorrow.

To help, here is a list of other datasets that could assist in understanding the effects that COVID-19 has had on our communities and inform recovery:

- Public transportation ridership data

- Demographic data

- Building permit and business license data

- Internet broadband usage data

- Social media and web search data

- Real estate and housing data

- Economic support application data

- Export and import data

If you have any questions about these datasets or others and their applications in understanding COVID-19 for your community recovery, please connect with us.