Beyond Vision Zero

Do Vision Zero programs actually work?

As agencies are underway in their multi-year efforts to institute policy, enforcement, and tactical changes in achieving vision zero goals, there have been several indications that these programs do have a positive effect.

For example, the City of San Francisco saw a reduction of 41% in traffic related deaths from 2014 to 2017

Vision Zero efforts primarily focus on reducing traffic fatalities and injuries. Since most traffic fatalities are caused by vehicles, agencies will focus on efforts that help reduce the likelihood of vehicle crashes causing deaths. The common prescriptions often introduced include:

- Reduction of speed limits and traffic signal timing changes

- Investments in Intelligent Traffic Systems

- Road safety measures (ie. installation of barriers and signs, pedestrian crossings with signal, sidewalk lengthening)

- Focus on traffic citations and enforcement of rules

- Awareness programs

In a perfect world, if there are zero fatalities or serious injuries, is that clear evidence that agencies have achieved their objectives? The answer is: it depends.

When Vision Zero efforts only focus on Vehicles and Road Operations

When vehicles (or the drivers) themselves are generally considered to be the cause of traffic-related deaths and serious injuries, it makes intuitive sense to create initiatives to focus on cars and drivers. Is it possible these initiatives only look at the symptoms rather than root causes?

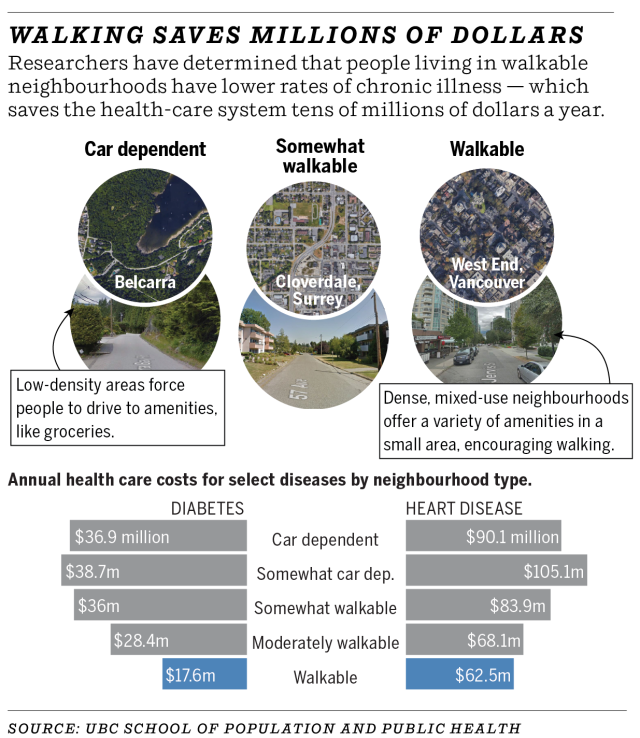

An agency that focuses on road design and sidewalk lengths could be ignoring:

- Zoning and land use changes resulting in increased pedestrian drivers and demand for biking

- Increasing pedestrian generators nearby dangerous intersections and major roads (parks, brewery districts, shared office spaces)

- Changing demographic makeup, gentrification and shifting mode-type demands (e-scooters, biking, transit use)

Agencies may potentially ignore the built environment and the changing urban landscape at their own peril. There is already evidence of this as traffic engineers struggle with estimating trip generation and traffic impact of new type of developments and business categories, with a potential over-emphasis on vehicles

As a result, Vision Zero effort successes could be short lived and fleeting.

The question becomes: Is it about creating an environment for pedestrians, bikers, and drivers to operate safely and in harmony?

Or is to recognize that in a world becoming more increasingly urbanized and simultaneously more millennial (and older), that focusing policy efforts just on vehicle and pedestrian safety is only an interim solution for longer-term problems for agencies?

Managing the multi-modal network and encouraging healthy lifestyles

In Sweden, the unintended consequences of Vision Zero efforts are being considered. For example, the use of wire cables to divide roads is attributed to fewer collisions and deaths but a reduction of access by cyclists to the road network, particularly in rural areas.

That would be an example of a policy decision that may reduce vehicle related deaths but lead to unintended impact on other agency and government objectives. Urban and community planning efforts often have objectives around designing safe, clean, and healthy communities.

“The goal of Moving Beyond Zero is to realize a transport system that promotes active mobility in the form of cycling and walking to improve quality of life and public health in addition to saving lives and reducing traffic fatalities and injuries”

Vision Zero Cities Journal

With climate change, the severe impacts of the 2008 global financial crisis, income inequality, technological changes, and changing priorities of a younger generation, the way that people move around their communities is fundamentally changing. In fact, North America may have experienced peak car ownership levels in 2018.

Agencies need to consider that Vision Zero efforts may be interim measures to help communities and cities ultimately transition to an emphasis on other modes of transportation with better community planning and design.

Wildcards – how the pace of technological innovation may scramble Vision Zero Plans

Many Vision Zero plans have been instituted by agencies in the early part of this decade. As with other plans generated by agencies in the public sector, the pace of technological innovation often throws these plans into disarray.

For example, within the last two years, the introduction of e-scooters and dockless biking programs has led to the creation of a new urban design paradigm – Mircomobility transportation.

As public servants and agencies struggle to come up with the right policies to manage the exploding popularity of these mode types, they need to contend with potentially increasing injury rates. In Austin, Texas, out of the 190 people injured in e-scooter accidents, half had head injuries.

As agencies institute a wide array of tactical decisions to make roads safer for vehicles, pedestrians, and bikers, it’s important to consider that these agencies will need to deal with underlying trends that are changing the way people move around in cities. From changing demographics to changing housing and transportation preferences, these trends can make vision zero objectives difficult to achieve and make any successes only temporary. While agencies strive towards zero traffic-related fatalities and injuries, it’s now more important than ever that these agencies have a holistic, adaptable understanding of their communities in a fast changing world.